Communication is an art and it is a skill that is hammered into us as clinicians. We are taught to ask open questions, demonstrate empathy and try to answer questions a patient may have. It’s tricky business really because as well as communicating and maintaining a professional attitude, we are also involved in trying to diagnose, investigate and manage patients.

Consenting for treatment is part and parcel of our practice. We seek consent for examining patients, performing blood tests, starting treatment and performing procedures. As part of this process we work to communicate risk to patients and this is certainly a rapidly evolving field.

2015 was a huge year for clinical practice. It had seen the conclusion of Montgomery v Lanarkshire which changed the entire landscape of consent. Prior to this clinicians would operate on a “need to know” basis of consent. In other words, a clinician would decide which risks are relevant for a patient and make them aware of these risks. Montgomery v Lanarkshire turned everything on its head.

So what happened?

Here's a summary of the case

Nadine Montgomery, a woman with diabetes and of small stature delivered her son vaginally who subsequently experienced complications owing to shoulder dystocia. This resulted in hypoxic insult with consequent cerebral palsy. Her obstetrician had not disclosed the increased risk of this complication in vaginal delivery, despite Montgomery asking if the baby’s size was a potential problem. He felt that the baby had almost no risk of having shoulder dystocia due to his specific factors (e.g. size). Montgomery sued for negligence, arguing that, if she had known of the increased risk, she would have requested a caesarean section.

Now what does this mean? This means that we should explain every single risk of any investigation or treatment we recommend. This definitely moves us away from a paternalistic outlook on clinical practice but may be slightly over the top (OTT) in a clinical setting. Take amlodipine for instance. I normally explain the risk of leg swelling with amlodipine and leave it at that. According to the outcome of Montgomery v Lanarkshire - we should be explaining every single side effect which is almost impossible in a 10 minute consultation!

So what do we do?

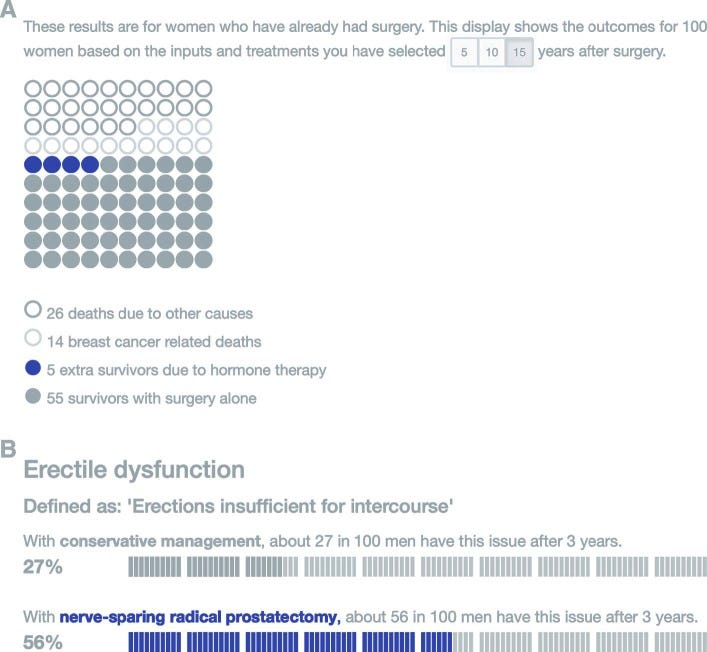

In light of the above, we should be extra careful in communicating and documenting risk. I think we all communicate risk in different ways and there’s no one-single way of doing so safely. Some people use numbers whilst others like to risk stratify as common, uncommon and rare. The key here is that in communicating risk, you are trying to convey an understanding of the risk involved. Patients need to be absolutely clear about the risk of a procedure/treatment and as a clinician it is your responsibility to ensure this.

I’ve recently started doing some reading around communicating risk and here are some useful tips:

Understand the problem and stats yourself: otherwise you will be deficient in your own understanding of risk and you will convey the info poorly.

Cut to the chase: patients like to be told about risks even before the benefit of a treatment.

Cater the information to your patient: would visual diagrams or bar charts help you illustrate this better?

Avoid speaking in absolute terms: Nothing is absolute in science and clinical management and talking in absolute terms would be unfair to your patient.

Back up your words with numbers: For instance, when non-medically trained people were told an adverse effect was ‘common’, they tended to think that it will happen around 50% of the time. Use a mixture of stats including percentages and risk ratios.

And finally, make sure you document your discussion(s) clearly. Ultimately it is your documentation that will stand up in a court of law.

Please share :)

Please like & share:

Check us out on our various pages

Website: www.paretoeducation.co.uk

Instagram: www.instagram.com/pareto_ed

Twitter: www.twitter.com/pareto_ed

Youtube: https://bit.ly/3DPm23c

Email: paretopaeducation@gmail.com